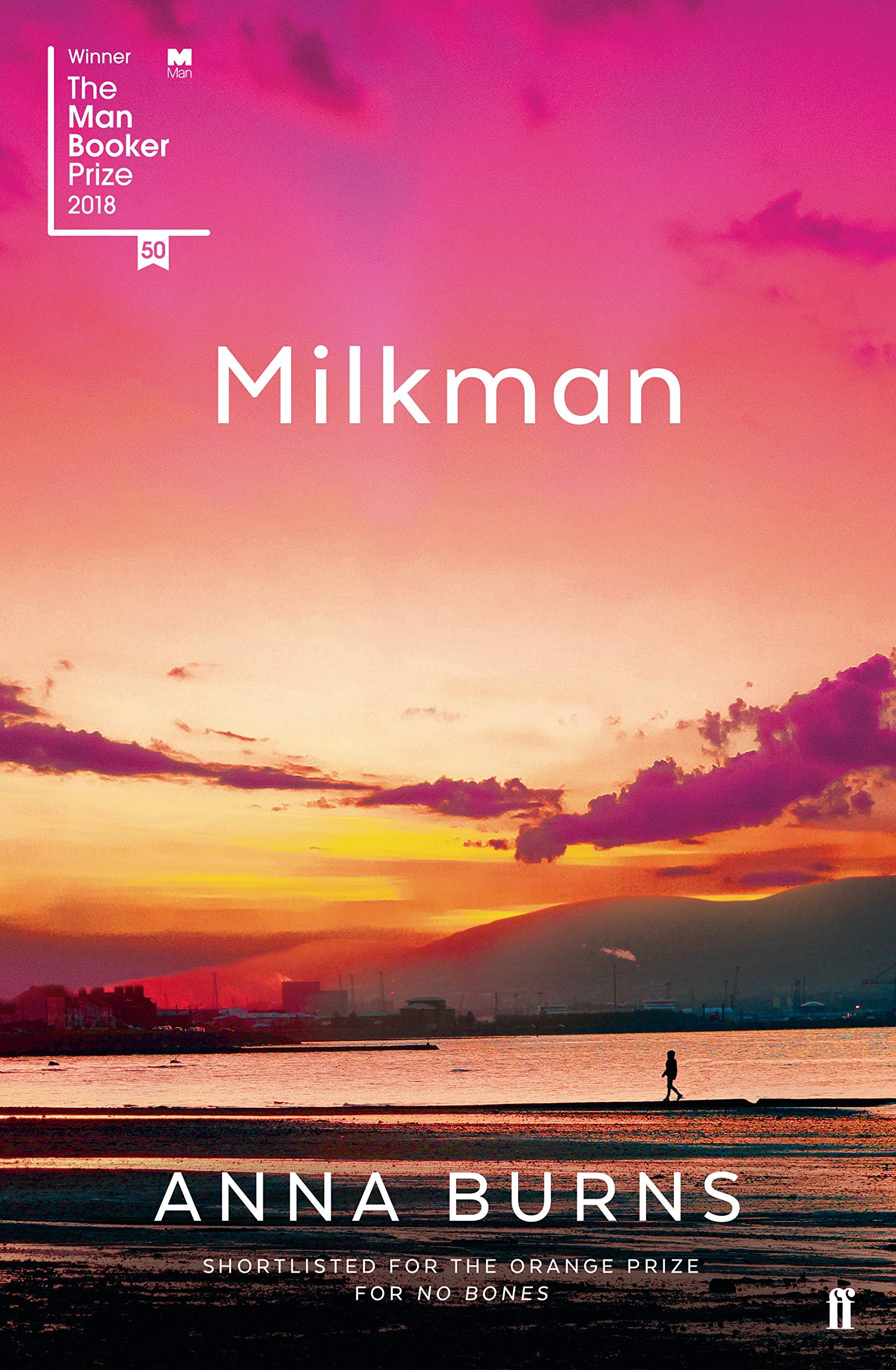

Milkman, Anna Burns

“It’s deviant. It’s optical illusional. Not public-spirited. Not self-preservation. Calls attention to itself and why—with enemies at the door, with the community under siege, with all of us having to pull together—would anyone want to call attention to themselves here?”

What does it mean to come of age during the Troubles?

Anna Burns’ 2019 Booker-winning novel Milkman - sharp, witty and abundant with rhetorical skillfulness - explores just that. Set in an unnamed Northern Irish city, a young, unnamed narrator navigates a cast of unnamed characters, referred to in colloquialisms such as, ‘Maybe-Boyfriend’, ‘Wee Sisters’, ‘First Brother-in-Law’, ‘Somebody McSomebody’, ‘Ma’, ‘Da’, and the foreboding ‘Milkman’. Burns refuses to acquiesce to names, labels, and political terms, constantly exploring the breadth and depth of implications.

Burns has crafted a stream-of-consciousness, coming-of-age, linguistic feat. Her language repeats, draws on, returns, ruminates; sentences are crowded and never-ending, creating a distinct Irish dialect and tone to great effect. Tapping into language, the carrier of a culture, in all of its local idiosyncracies, is a remarkably intelligent way to explore larger political issues.

The titular ‘Milkman’ is not really a milkman, but a prominent dissident, a paramilitary, a violent renouncer. And he has decided to pursue the novel’s young narrator, to claim her as a sexual object of his own. She reads books while walking, is in a relationship with a ‘Maybe-Boyfriend’, takes french lessons, goes drinking, and generally survives life in a dangerous and troubled city with a stark normality and apathy to the violence around her. She is warned by her townfolk of the ‘deviance’ of her reading whilst walking, that it ‘calls attention to itself’. She is forced to endure the looming presence and threats of Milkman, being the senior paramilitary figure that he is.

Most of the mas in this town have lost sons, daughters, and husbands; death is frequent and expected, the Troubles interwoven into the fabric of everyday life. “The right butter. The wrong butter. The tea of allegiance. The tea of betrayal.” But the driving force of day-to-day life, and in turn the novel, is gossip and rumours and chatter; it is a kind of scrutiny and tribalism that is a result of rigid political and religious divisions, a societal kind of policing.

Editorial Picks