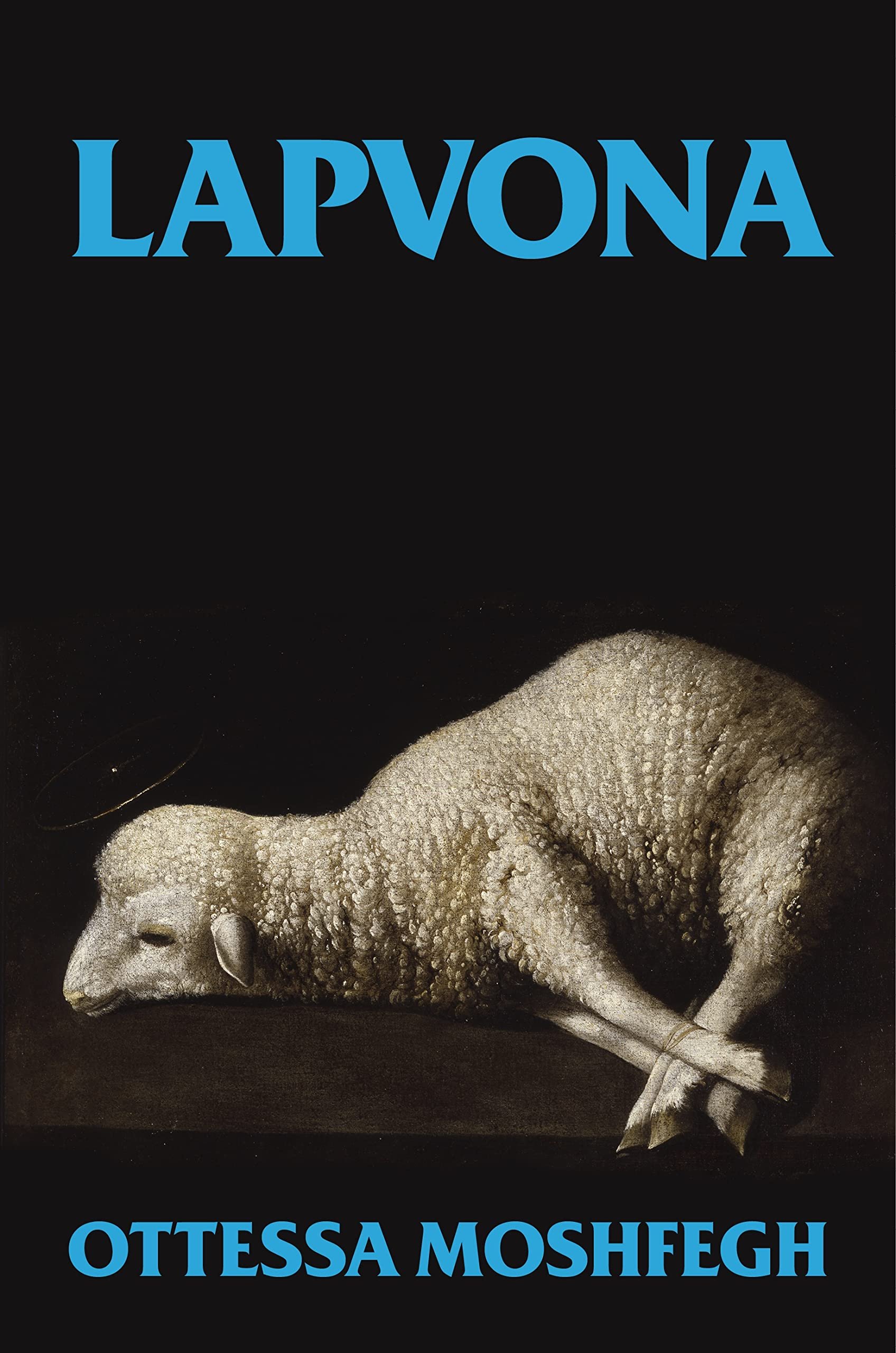

Lapnova, Ottesa Moshfegh

“Lapvona is sure to be a polarising work, exposing the reader to the uncomfortable and the grotesque, and so it should be approached with a strong stomach and an open mind.”

Ottessa Moshfegh is unique in her ability to challenge the worldview of the reader, and to make them sit in the uncomfortable parts of human nature.

It speaks to her literary confidence to release something as sullen and pastoral as Lapvona following the recent proliferation of her cruelly chic favourite, My Year of Rest and Relaxation. While both novels differ vastly in content, they both have received her seal of sharp and unforgiving social commentary that gives her writing that distinctive grit. Lapvona is a somewhat long term project for Ottessa, and contains some of her strongest writing so far.

Lapvona is the name of our medieval fiefdom, ruled by the negligent Lord Villiam, who presides over his subjects with the help of the corrupt town priest and a secret collusion with the town bandits who use violence to keep people in line. Here we meet Marek, a boy born with a physical disfigurement who grows up on a sheep farm with his father, Jude. Marek’s life is lacking in emotional indulgence of any kind: his father is a violent man who believes that self-flagellation is the route to heaven, and his mother is thought to be dead. When there is an accident involving Lord Villiam’s son, the circumstances of Marek’s life change, as he finds himself adopted by the strange patriarch of the village, and a pernicious drought affects the people who are left to survive while resources are hoarded by the castle above.

Her previous novels have been insular in narrative style, focusing on the complex inner life of her protagonists: the devastatingly cruel unnamed narrator of My Year of Rest and Relaxation, the violently lonely Eileen, and the unwaveringly proud Vesta in Death in her Hands. While Lapvona follows Marek for the most part, she trades in this internal investigation for a societal one. She looks at her central characters in less eviscerating detail, while looking in more depth at how they are failed by authority figures, and how they fail each other as a result. Elements of this style change reminded me of The Discomfort of Evening by Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, or Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor in their analysis of close knit communities dependent on religion to give meaning to suffering. Literarily, it was the expansion of her abilities that I thoroughly enjoyed reading.

I have a loose theory that if you look closely at Moshfegh’s novels, you’ll recognise a recurring theme of sin. The sin that Lapvona dissects is greed. Following the pandemic and the ever-worsening climate crisis, Moshfegh’s observations on class segregation, resource hoarding, and negligent leadership become all the more pertinent. By sectioning the book into seasons, Moshfegh reminds us of the precariousness of human survival, heightened by the novel being set in a medieval time period. In the summer section, there is a sense that something is out of balance; this is a time when nature should be thriving, yet Lord Villiam has begun hoarding water and crops. The silent death and suffering of the townsfolk is written by Moshfegh in a passive yet violent way – aggressive in its implication. The medieval fiefdom makes for a simple class analysis, as the complex structures of modern life are stripped to their basic truths. Lord Villiam teeters on the tightrope between being laughingly absurd and pure evil, colluding with the priest in a way that is sickeningly reminiscent of the dangers of the mutual interest between church and state. A quietly furious tension brews among the townspeople that is sure to bubble over, although the fear of instability generally triumphs.

The way that Moshfegh explores femininity is always interesting, and her work usually centres on female protagonists; however, Lapvona presents a vacuum of feminine traits. Moshfegh doesn’t criticise the women for their neglect of duties as wives and mothers; instead, she implicates a societal structure where they are necessary to counteract the viral hyper-masculinity that leads to the hellish prototype of capitalism that props up Lapvona. The women refuse to perform emotional labour, to love and raise children inflicted upon them by abuse, to pour nurture from an empty cup. From my perspective, Moshfegh is exploring the delicate battle that exists between collective survival and personal liberation.

Lapvona is sure to be a polarising work, exposing the reader to the uncomfortable and the grotesque, and so it should be approached with a strong stomach and an open mind. Even so, I always trust Moshfegh to lead me into such dark pitfalls of humanity, as I know I will emerge with a deeper understanding of where we are, and how we can heal.

Featured in the Exploration Issue

Editorial Picks