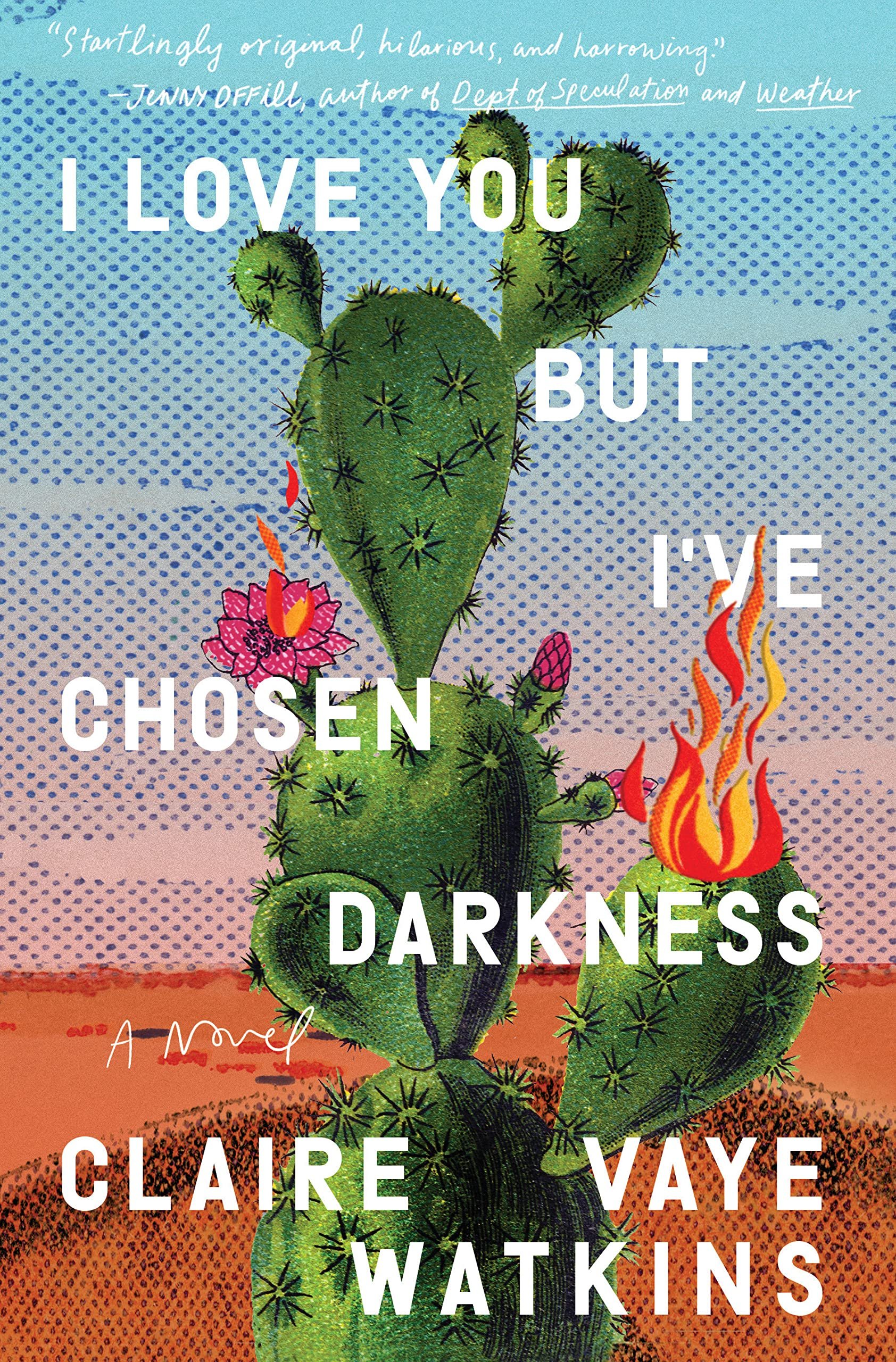

I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness, Claire Vaye Watkins

‘Watkins writes compassionately about maternal ambivalence, and the ‘sludgy era of despair, bewilderment, and rage’ that may follow childbirth.’

In this her third book, Claire Vaye Watkins seamlessly blends fiction and autobiography. Her narrator, a writer also named Claire Vaye Watkins, is suffering from severe post-natal depression. Following a lecture-trip to Reno she impulsively abandons her college teaching job, her comfortable house, husband and baby daughter, and retreats to her native California. There she attempts to come to terms with her past, and to forge a new life.

Watkins writes compassionately about maternal ambivalence, and the ‘sludgy era of despair, bewilderment, and rage’ that may follow childbirth. However, her multi-faceted book is much more than an account of post-natal depression and its aftermath; it is a poignant elegy for her father Paul (a one-time acolyte of Charles Manson), her mother Martha (‘an artist, a naturalist, a writer’) and her gentle ex-boyfriend Jesse whose tattoo gives the book its title. It is a gripping account of her journey from ‘being raised by a pack of coyotes to a fellowship at Princeton’. It is an enthralling odyssey across Nevada and California, as her narrator searches for love, identity and a place to call home. And there are abundant memorable descriptions of the American West: the gem mines of Death Valley ‘splashed with turquoise, aquamarine, smears of amethyst’; the ‘vice capital’ Las Vegas with its ‘shallow memory’; the ‘ecstatic cold’ of the wild springs at Tecopa.

Some aspects of the book are less successful. Martha’s teenage letters (confusingly given in reverse chronology) tell a rather monotonous tale of adolescent self-destruction, while the narrator’s drug trips feel self-indulgent, as do her claims to have grown vaginal teeth. But the novel sustains its interest thanks to Watkins’s narrative skill and luminous prose style – both of which promise much for the future.

Editorial Picks