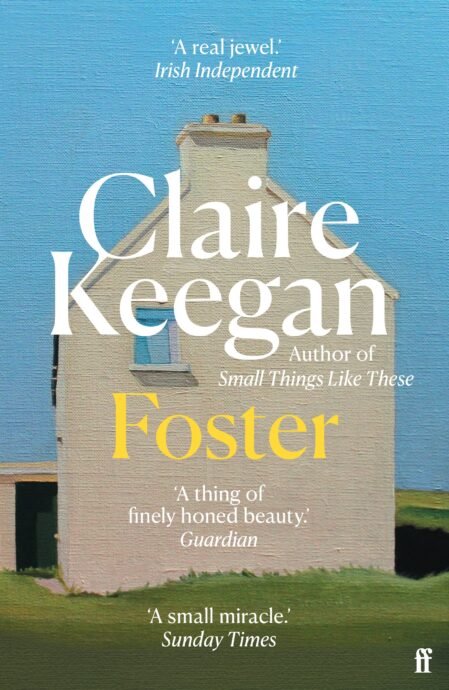

Foster, Claire Keegan

“This is a different type of house. Here there is room, and time to think.”

Good juvenile narratives often belong, at least in mind, to the classics: Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Carson McCuller’s The Member of the Wedding, J. D. Sallinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Claire Keegan’s unnamed child narrator in Foster is imbued, in the same lieu, with distinguishable idiosyncrasies and a personable dialect, putting her amongst this array of canonical figures.

In this slim novella, which has its foundations as a short story in the New Yorker, the protagonist is left by her father at the home of some distant childless relatives in county Wexford. He doesn’t hang around to say goodbye, eating and taking his leave, his affection for his child notably absent. The new house and foster parents John and Edna Kinsella are immediately warm and homely, the child remarking, “this is a different type of house. Here there is room, and time to think”. Across its pages, the book is both immediately and increasingly grounded with a sense of place and home. The surroundings are comfortingly pastoral, abundant and fruitful, motherly somehow. Village life is ordinary, full and exciting in the child's eyes, despite the prying eyes of its inhabitants. Language is both lyrical and straight-to-the-point.

The child observes and says little; meaning lies more in what is unsaid and not understood. There is always a lack of comprehension that accompanies the trope of young narrators, where it takes a bit more work to read between the lines, and the skill of a great writer.

Editorial Picks