A Conversation with Sarah Bernstein

“This is part of the point of not locating the story in a particular place, of building up a sense of timelessness: establishing a sense that history is ongoing, the past is ongoing, it continues to reverberate, to be felt, in the present.”

First, could you tell us a little bit about the experience of writing and publishing Study for Obedience, and then how it felt to be shortlisted for the Booker?

I had been working on pieces that formed the basis of Study for Obedience for a couple of years before I realised they were part of the same project. Once I realised I had the basis for a voice, I took some time off writing to read and think with this voice in mind. I came away with a sense of what the story might be, and the central dynamic of the brother and sister, and from there it came together quite quickly. The publishing process was slightly less straightforward, as quite a few publishers turned it down before Granta took it. I’m very grateful that they did. I like the book I wrote and take my work seriously, but it never occurred to me that it would be considered for any kind of prize at all.

I read that the sound and rhythm of your words are an incredibly important aspect of your writing. Could you tell me a little more about that, and how it changes the way you approach your writing?

It’s an approach I think I have always taken intuitively but never really articulated to myself or anyone else until my first novel came out and I found myself having to talk about process. I don’t work at the outset at least, with a clear plan for a sequence of events. I start with voice, the sound of the narrator’s voice. So, I’ll start with a sentence or a part of a sentence, like catching a musical phrase, and follow the logic of the sound of that sentence as far as I am able to. Alongside this and helping to shape its course are feelings that animate the work—my own feelings at the time of writing as well as the kind of affective landscape I envision for the work—and ideas about setting, atmosphere, story, concepts, and so on. I say ideas but maybe what I mean is impressions—almost like a mood board. I keep a notebook.

What were your main literary influences for this book in particular? And on your writing style in general?

It’s difficult for me to tease out specific literary influences for a piece of writing, in part because I see all of my writing as made up of all the things I’ve read before, but I also understand these influences to be under the surface—that is, not necessarily mobilised deliberately. Having said that, I think there’s something to be said for proximity, so some of the writers I’d been reading a lot of around the time of writing include Marie NDiaye and Shirley Jackson, and essays by Laura Riding. In terms of style in general, the first novel I really loved as an adult was James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room. I think I read that book probably once a month for many years. When you read a novel like that, so intensively, so many times, it must create grooves in your imagination, in your way of thinking and writing. Around the same time, I read a lot of Thomas Bernhard’s writing, and although I haven’t read his work in over a decade, it too had an outsized influence on how I thought about writing at the level of the sentence. I think, though, that I am a modernist at heart: I love Virginia Woolf and Zora Neale Hurston and Gertrude Stein and Jean Toomer and Samuel Beckett. I am drawn to writers who expand the possibilities of what literature can or ‘should’ look like, like Theresa Hak Kyung Cha and Leslie Marmon Silko. Reading over this answer, I realised this list is actually just most of the syllabus for a course I taught on literary difficulty a few years ago. It’s funny, because I imagine that a writer’s personal archive of texts is always changing, and yet there are writers we come back to again and again.

One thing that really caught my attention in Study for Obedience was this sense of timelessness, which was emphasised by the fact that the location was also nameless and unknown. Could you tell us more about that decision and how you hoped it would affect the reader’s experience?

In the case of this novel, whose central character comes from a Jewish background, I wanted to try to resist the almost inevitable reduction of Jewish history and Jewish identity to the Shoah, using the Shoah as the primary explanatory framework for these things. There is something thought-terminating about the absoluteness of this association, which is made both by non-Jews who don’t know very much about Jewish history but think they do, and by Jewish people who almost certainly should know better. It’s a difficult association to break, partly because, for non-Jews, the Shoah made newly available a conception of the Jew as a figure of suffering and sympathy, rather than merely a figure of suspicion and contempt. But as I’ve said elsewhere: Jewish history did not begin with the Shoah, just as the conditions already existed and continue to exist that enable people to do horrible things to one another—the Shoah, terribly, has what Pankaj Mishra describes as a ‘universal salience’.

What I wanted to do with this book was to explore a specific experience of history as a series of catastrophes, each sitting in the last and prefiguring the next. I wanted to explore how this sense of history works on the body and in the mind of a particular character. What does it mean to pass down such an experience of history? What kind of person might that create, capable of what actions? What would it mean for their horizon of possibility, their sense of their own agency, their ability to act in the world? This character, despite her obvious flaws, has a sense that her people’s history of victimisation is intertwined with those of other people: it does not lend her a special and permanent innocence, it does not absolve her of agency, or of guilt. At the end of the novel, she says ‘So much was refused in advance. So much transpired on a scale of time and space that was longer than a lifetime, wider than a country, vaster than the story of the exile of a single people. And bigger still.’ Her story is her own, it is inflected in particular ways, but equally, it is not an experience that is exclusive to the Jewish people

This is part of the point of not locating the story in a particular place, of building up a sense of timelessness: establishing a sense that history is ongoing, the past is ongoing, it continues to reverberate, to be felt, in the present. It continues to structure the world, relations with other people, and individual experience.

Your unnamed narrator lives her life very much through the idea of obedience, which brings up so many questions and tensions between the ‘innocence’ and culpability of unwavering dedication. Why was this something you wanted to explore through fiction, and what was it about the idea of obedience that made you want to delve deeper into the subject?

Years ago, I went to a retrospective of Paula Rego’s work in Edinburgh, and she was quoted on the gallery wall saying that the women in her paintings could be ‘obedient and murderous at the same time’. I became interested in the potential for obedience, which we understand as a passive, often feminised, characteristic, to carry some form of agency, even power. I had been thinking about this for a few years, and it’s something that my friend Daisy Lafarge explored in her novel, Paul: a passivity that is so absolute that it takes on its own kind of power.

I wanted to unpick idea that ‘innocence’ is a stable, permanent category of being that is granted by having badly treated oneself, and to explore how such innocence can be weaponised. And then I wanted to think about why, in order for us to be able to understand someone as having been victimised and to extend our sympathy we need to see them as ‘innocent’. The former should not depend upon the latter, and yet in our world it does—I’m interested in how innocence gets constructed, who is afforded a position of innocence and therefore comes to be seen as deserving of sympathy.

The narrator also displays the instinct to live her life only in relation to others – her identity and actions seem to be dedicated to her from others more than her own self. Would you say that she exemplifies an extreme version of an instinct that is in all of us?

Certainly, this is a character who looks to the outside world, to other people, to social scripts, to literature, for instructions on how to live, and she does take this to an extreme. She can’t imagine for herself what her life might look like. Maybe this is a kind of pathological version of the process by which people are interpellated into the existing social order. I have been thinking about this a lot especially since having a baby because so much should be possible, but so much is determined and refused in advance. The baby could do anything, be anything, feel anything. But I can see the world, other people’s expectations, my own patterns of being, weighing down already, how that process of paring down and defining is already beginning.

There’s an eerie, ghostly feel to this book without there being any explicit ghostly activity. Why did you choose this ghostly atmosphere and how do you think it might relate to your narrator’s character or situation?

If there is a ghostly atmosphere, it is probably because of the book’s interest in the ongoingness of the past, the way the past lives on in the present, shapes the present. There is also the fact of the central character coming to see her presence in the town as a kind of ghostly, unwelcome one. She senses that she reminds the townspeople of a shameful past that they don’t want to remember.

Which book or books are you reading at the moment?

I’m reading Death Styles by Joyelle McSweeney and Saidiya Hartman’s Lose Your Mother.

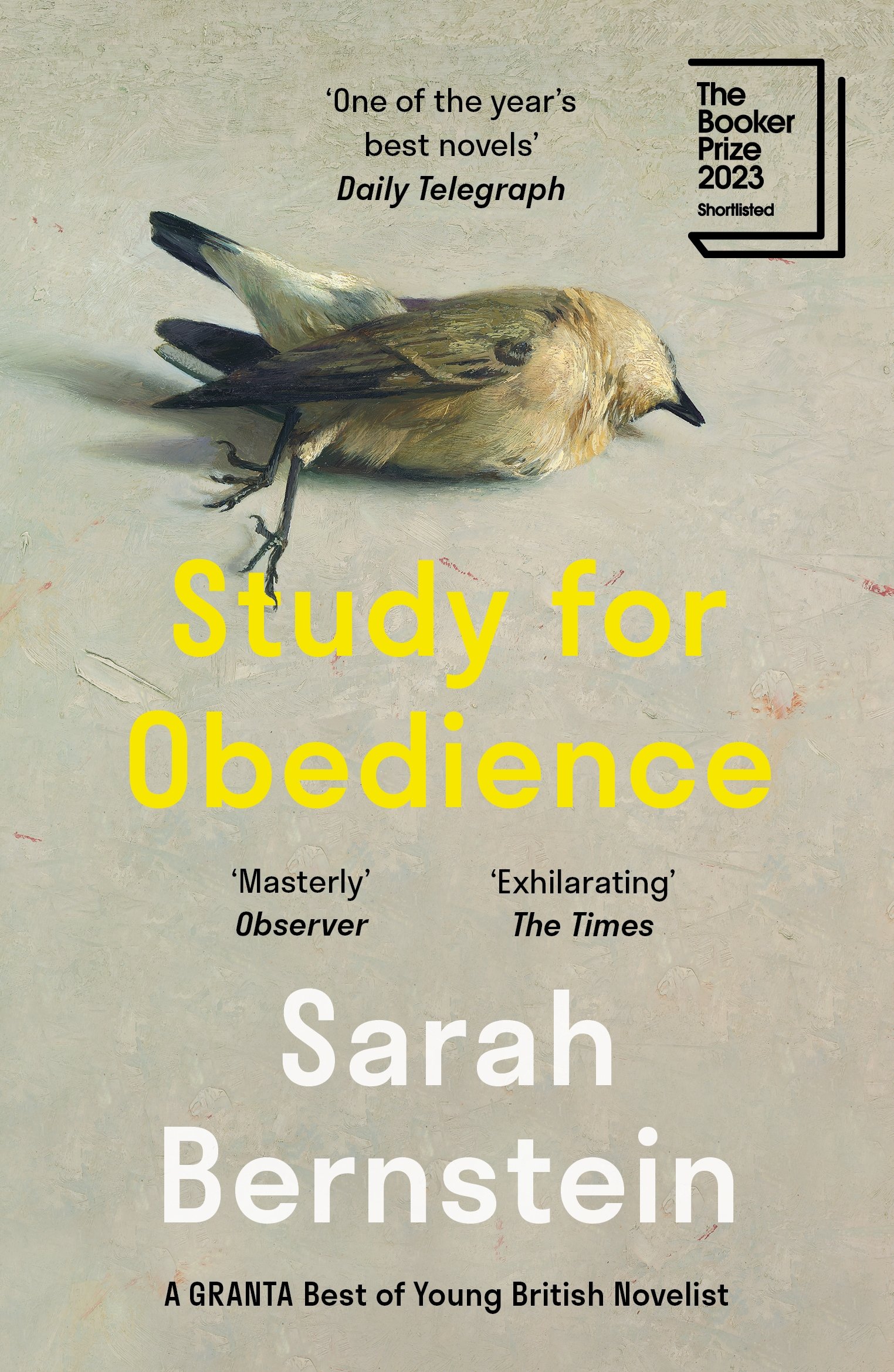

And lastly, do you judge a book by its cover?

I don’t, mostly because I tend to seek out books that I’ve read about in other books or heard about from friends or on podcasts, and if I end up liking those books, I’ll pursue those writers and their thinking in a slightly dogged but also meandering way, setting myself on a course to read everything a writer has written and then also finding myself distracted by work these writers introduce or bring to mind. I get so involved with all this that there’s hardly any time to browse for books I might judge by their covers. I do appreciate good design, though.

Editorial Picks